Since 1930, Camp Rising Sun has shaped the lives of more than 6,500 alumni from over 60 countries. Across generations and continents, CRS alumni continue to lead with empathy, curiosity, and courage—bringing Camp’s values into classrooms, courtrooms, creative industries, clinics, and communities.

As we celebrate 95 years of impact, we’re spotlighting just a few of the many stories that show how a summer at Camp becomes a lifetime of meaning.

Please visit lajf.org/crs95 to learn more about our 95th Anniversary Celebration from October 24-26.

Richard Gibbs (CRS ‘63)

Dr. Richard Gibbs, who attended Camp Rising Sun in 1963, dropped out of Harvard to join a professional ballet troupe and toured the world with different ballet companies for more than a decade. He eventually returned to Harvard, then studied for a degree in medicine at Yale where he met his wife Tricia. Both doctors, the couple formed a practice — the San Francisco Ballet Medical Program — to treat dancers. Concerned over the high number of people with no health insurance, they went on to found the San Francisco Free Clinic in 1993.

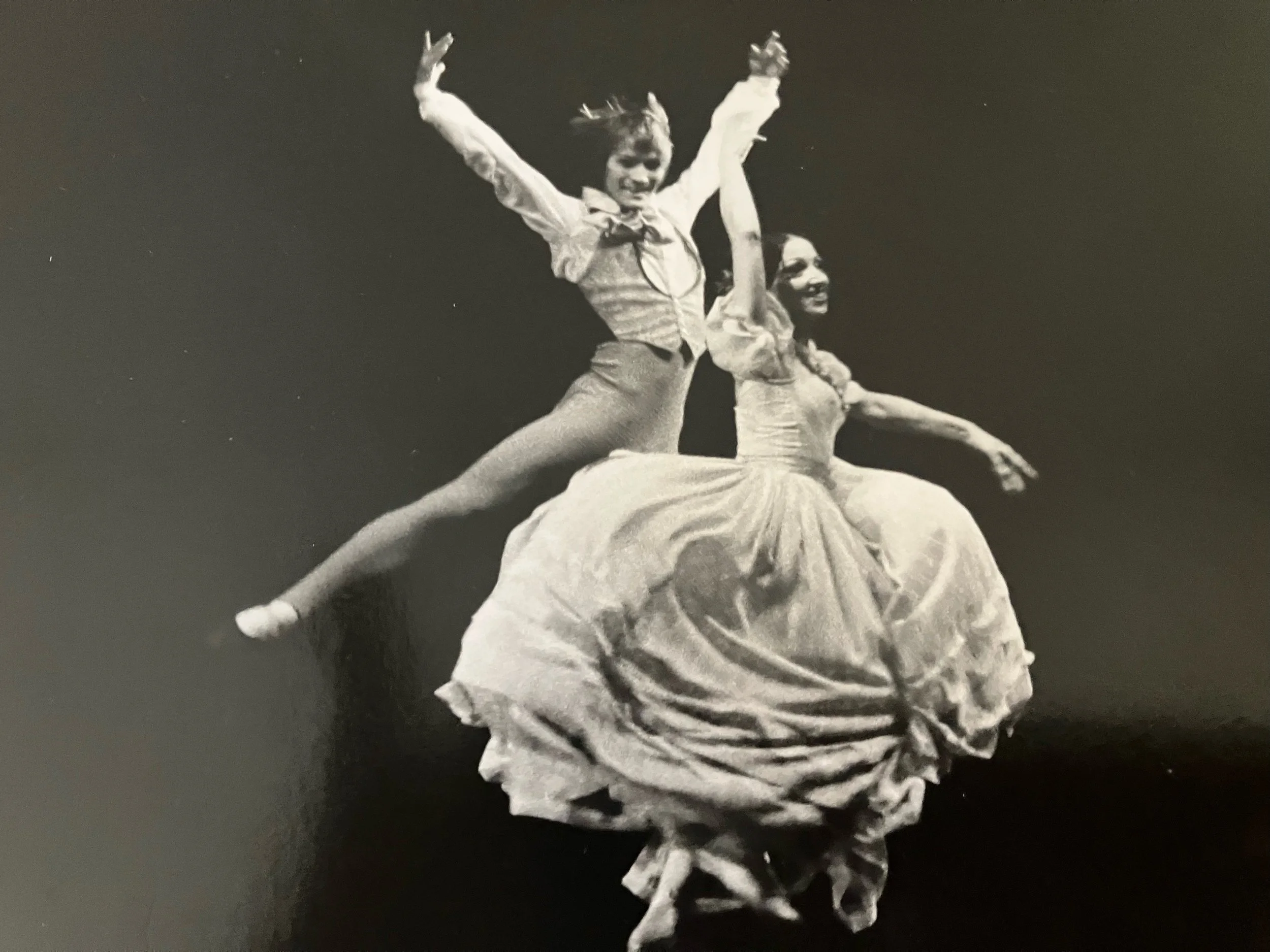

Gibbs and Sara DeLuis from First Chamber Dance Company, circa 1980.

I went to high school in upstate New York, which is where I met George E. “Freddie” Jonas. At the time I just understood that he was the director of a summer camp called Camp Rising Sun, and that he was looking for boys from all around the world he thought might make good candidates to be future leaders in business, society, science, the arts, and government — a foundation of his camp’s mission.

Freddie interviewed us at the high school, and all of a sudden I had an invitation to go to Camp Rising Sun. I’m not sure what he saw in me, but I figured Camp might be just a good time — typical outdoors stuff, recreation and a bit of camaraderie. I was in for much more than I bargained for — in a good way. The two months of summer spent at a woodsy stretch of land in Rhinebeck, New York, would inform my career, help me navigate challenges, and develop in me a passion to help others.

When I arrived that summer of 1963, I found that half the campers were from all over the globe.

We were all in tents with wooden floors and six cots. And every week, you'd change tent mates so you got to stay up at night talking with boys from all over the world with different views on life. It was in these conversations I would learn simple things like the difference between Finland and Sweden. I remember there was a camper from Greece and one from Turkey—two countries that were at war at the time. And then there would be more intense discussions on religion and politics — and yes, girls. It made me wonder if I already had preconceived notions on these topics, and if I did, should I be working around my newfound perspectives to see how my thinking might change.

We were assigned chores each morning — such as building a trail in the woods, working on a swimming hole, or building a camping platform. The boy from Finland was a carpenter, and I assisted him in helping rebuild a stage.

After the chores, we had “Instructions” taught by the campers themselves. The word instruction makes it sound like something rooted in reading, writing, and math but in reality it could be any learning experience. If a boy was a fencer, he'd give an hour or more program on fencing. Somebody else would do a talk about Mozart operas.

Already interested in dancing and the arts, I naturally fell in with those types of projects. We did a lot of plays. My first week I directed a reading of Oedipus Rex and did a major show of Henry IV, Part 1. There were musicals in the evening — I remember that I played the clarinet back then and tackled part of a Mozart concerto, while a camper from Egypt accompanied me on piano.

The counselors were also very influential and they were all former campers themselves. We understood that there would be no berating or bullying of other campers, that what we were working toward was never out of self-interest but instead a collaboration that would make Camp an even better place — and the realization that these skills could then extend to our lives and to those around us.

Here is where Freddie’s genius shone. When he started Camp Rising Sun in 1929, he realized fifteen is a very idealistic age. Bright young people are looking at the world with a lot of hope and with a positive attitude. So, it's the perfect age for encouraging two things: one, ethics, which was built into the experience, and two, getting you to think about what kind of leadership you might assume in society.

After I left Camp, I attended Harvard but dropped out to continue my pursuit of being a ballet dancer. My father was not enthusiastic about the prospect, but I forged ahead and got a scholarship to Joffrey Ballet School where I studied hard for about three or four years, then broke into my first ballet company.

Gibbs treating dancer Tina LeBlanc, San Francisco Ballet, at his clinic.

I toured a lot — 180 shows a year, sometimes seven shows a week — all through South America, Central America, and Cuba. Then I got an offer to go to Hamburg. We'd perform in Paris, Venice, Milan, and Vienna, and we were constantly on the road.

Hitting my mid 30s, I thought, “Do I really want to just teach ballet the rest of my life?” — which was the next likely step for me as I aged. I often combatted feelings that I was being selfish for pursuing a life in the arts. Sure, ballet is a vehicle of storytelling that can enrich others’ lives, but it’s not like feeding the hungry in a war zone. But I looked back on Camp Rising Sun — with so many arts-focused projects I participated in — as giving me the confidence to pursue my dancing career. And in a way, I stopped feeling selfish for fixating on my ballet career.

But I also realized that there might be more in store for me in helping others, and that I needed to take the initiative to make it happen. I went back to Harvard to finish my undergraduate degree and began to focus on a new idea: to treat dancers in ballet companies, because they're often prone to injuries. With that goal in mind, Yale accepted me as a medical student, and that's where I met Tricia, my future wife.

She had been on the U.S. Ski Team and we were both much older than the rest of the Yale medicine class by a good 12 years or so — that threw us together because we were sort of the oddballs of the class. After completing our medical degrees in family medicine, Tricia and I created the San Francisco Ballet medical program to take care of ballet dancers and I stayed on as their leading doctor.

We were working in a city where one in four people did not have health insurance. That’s where my experience at Camp Rising Sun came in again. I would take the lead — or attempt to — in doing something for people who were not poor enough to qualify for free healthcare but not making enough to be able to afford private insurance.

Eventually, Tricia and I decided to open a free clinic for people without health insurance — the San Francisco Free Clinic. Drug companies donated medications, hospitals donated X-rays and MRIs, and it snowballed into this very successful, small, modest, but free clinic for people.

As much as I love dance, it's been so fulfilling to be a doctor and realize the satisfaction of operating a free clinic. It was just a warm, fuzzy place. And Camp Rising Sun played an important role in both of my passions.

I follow Camp Rising Sun through its emails and make a gift every year — both to relive cherished memories, and also as a way of saying thanks, with the hope that it inspires other people to become leaders for good in the world.